RECORDING OF JULY 10 BOOK TALK IN THE JOHN DREW THEATER

The next great innovation revolution: CRISPR, gene editing, and Jennifer Doudna

The bestselling author of Leonardo da Vinci, Einstein, and Steve Jobs returns with a gripping account of how Nobel prize winner Jennifer Doudna and her colleagues launched a revolution that will allow us to cure diseases, fend off viruses, and improve the human species.

Bestselling author Walter Isaacson has established himself as the biographer of creativity, innovation, and genius. Einstein was the genius of the revolution in physics, and Steve Jobs was the genius of the revolution in digital technology. We are now on the cusp of a third revolution in science, a revolution in biochemistry that is capable of curing diseases, fending off viruses, and improving the human species itself. The genius at the center of his newest book, The Code Breaker(available on March 9, 2021), is American biochemist Jennifer Doudna (pronounced DOWD-nuh), who is considered one of the prime inventors of CRISPR, a system that can edit DNA.

Doudna’s story begins when she was a sixth-grader in Hilo, Hawaii, and she came home from school one afternoon to find a book on her bed. It was The Double Helix, James Watson’s account of how he and Francis Crick had discovered the structure of DNA, the spiral-staircase molecule that carries the genetic instruction code for all forms of life. Doudna put the book aside, thinking it was a detective tale. When she read it, she discovered that she was right, in a way. As she sped through the pages, she became enthralled by the race to put together clues, both in competition and cooperation with other scientists, that culminated in the 1953 discovery of the building block of life. Even though her high school counselor told her girls didn’t become scientists, she decided she would.

The structure of DNA was the 20th century discovery that would have the most effect on the 21st. But at first its impact was somewhat underwhelming. Beginning in 2006, Jennifer Doudna helped change that. Her studies focused not on DNA, a field dominated by men, but on what seemed more of a backwater in biochemistry: figuring out the shapes and structure of RNA, a closely related molecule that enables the genetic instructions coded in DNA to express themselves by directing the creation of protein for new cells.

Driven by a passion to understand how nature works and to turn discoveries into inventions, she would help to make what James Watson told her was the most important biological advance since his co-discovery of the structure of DNA. She and her collaborators turned their curiosity into an invention that would transform the human race: an easy-to-use tool that can edit DNA. Known as CRISPR, it opened a brave new world of medical miracles and moral questions

“This year’s prize is about rewriting the code of life,” the secretary general of the Royal Swedish Academy proclaimed in announcing that Doudna and her collaborator, Emmanuelle Charpentier, had won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. “These genetic scissors have taken the life sciences into a new epoch.”

The Moral Dilemma

With The Code Breaker, Isaacson shows what it took for Doudna to defy the odds as woman in a male-dominated field. His gripping narrative twists and turns through the risks she took, the rules she broke, the alliances she formed, the competition she bested, and the moral dilemmas she faced along the way. After helping to discover CRISPR in 2012, Doudna became a leader in wrestling with the ethical implications of this invention and helping set up the guardrails we are going to need as a civilization.

Because at the core of this book is a moral dilemma: Should we use our new evolution-hacking powers to eliminate dreaded disorders like Tay-Sachs and sickle cell anemia? Should we edit our genes to make us less susceptible to deadly viruses? And what about preventing congenital deafness and blindness? Or being very short? Or being depressed? Should we allow parents to enhance the IQ or memory or muscles of their kids? Our newfound ability raises some uncomfortable questions about what might that do to the diversity of our societies. If these offerings at the genetic supermarket aren’t free (and they won’t be), will that greatly increase inequality—and indeed encode it permanently in the human race?

In 2018, the world’s first “designer babies” were engineered and born: twin girls in China with genes that had been edited with CRISPR to make them immune to the virus that causes AIDS. There was an immediate outcry of shock and awe. After three billion years of evolution, one species (us) had developed the talent and temerity to grab control of its own genetic future. There was a sense that we had crossed the threshold into a whole new era, like when Adam and Eve bit into the apple or when Prometheus snatched fire from the gods.

Doudna has been at the forefront of scientists who are grappling publicly with these moral issues. At one point when she was developing CRISPR, Doudna had a nightmare in which she was summoned to meet a powerful client who wanted to learn how it worked. When the client looked up, it was Adolf Hitler. That spurred her to become a key organizer of groups that are trying to find a path forward that allows CRISPR to fulfill its promising potential while preventing it from being misused.

The Coronavirus Vaccine

Most recently, however, Doudna and the other pioneers of CRISPR have been deployed in the war against our most immediate threat—the coronavirus—and Isaacson brings readers up-to-the-moment reporting on that fight. The gene-editing tool that Doudna and others developed in 2012 is based on a virus-fighting trick used by bacteria, which have been battling viruses for about three billion years. CRISPR systems allow bacteria to remember and then destroy deadly viruses. In other words, it’s an adaptive immune system against viruses—just what we humans need in an era that has been plagued by repeated waves of viral epidemics.

From the moment COVID-19 emerged, catching the federal government flatfooted, Doudna recast her team’s gene-editing system to develop a scalable and reliable test for the virus, with the eventual bigger goal of making us invulnerable to the future ones coming our way. Up until COVID-19, Doudna and her rivals were elbowing each other out of the way to get ahead in the race for CRISPR and other big discoveries. But when the pandemic hit, they put their competition aside and locked arms in the race to save lives. CRISPR has since enabled new forms of testing and treatments, and it has helped with the creation of an easily reprogrammable vaccine that can quickly be tailored to any new virus that comes along.

The Code Breaker tells Jennifer Doudna’s story, a thrilling scientific tale that involves the most profound wonders of nature, from the origins of life to the future of our species and carries the urgency of meeting the crisis we face today. As Isaacson writes, “the development of CRISPR and the race to fight coronaviruses will hasten our transition to the next great innovation revolution: a life-science revolution. Children who study digital coding will be joined by those who study the code of life.”

-

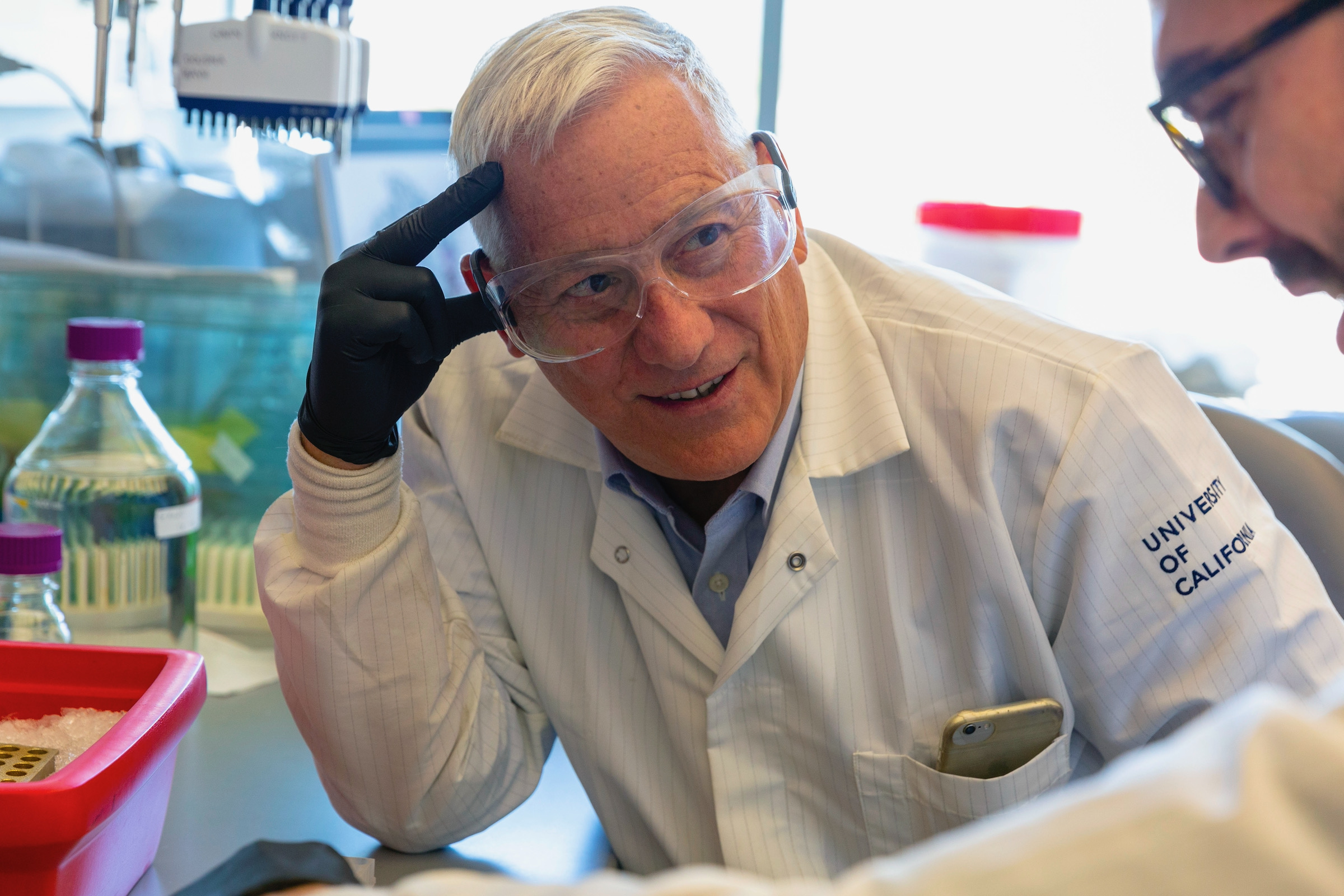

Walter Isaacson

Walter Isaacson, a professor of history at Tulane, has been the CEO of the Aspen Institute, where he is now a Distinguished Fellow, the chairman of CNN, and the editor of TIME magazine. He is a host of the show “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and CNN, a contributor to CNBC, and host of the podcast “Trailblazers, from Dell Technologies.” He is also an advisory partner at Perella Weinberg, a financial services firm based in New York City.

Isaacson is the author of The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race(2021), Leonardo da Vinci (2017), The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution(2014), Steve Jobs (2011), Einstein: His Life and Universe (2007), Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (2003), and Kissinger: A Biography (1992), and coauthor of The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made (1986).

Isaacson was born on May 20, 1952, in New Orleans. He is a graduate of Harvard College and of Pembroke College of Oxford University, where he was a Rhodes Scholar. He began his career at The Sunday Times of London and then the New Orleans Times-Picayune. He joined TIME in 1978 and served as a political correspondent, national editor, and editor of digital media before becoming the magazine’s 14th editor in 1996. He became chairman and CEO of CNN in 2001, and then president and CEO of the Aspen Institute in 2003.

He is chair emeritus of Teach for America. He was the vice-chair of the Louisiana Recovery Authority, which oversaw the rebuilding after Hurricane Katrina. He was appointed by President Barack Obama to serve as the chairman of the Broadcasting Board of Governors, which runs Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, and other international broadcasts of the United States.

He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Royal Society of the Arts, the American Philosophical Society, and the Society of American Historians, of which he served as president in 2012. He serves on the board of United Airlines, Halliburton Labs, and Bloomberg Philanthropies.