A look back at some of the great moments in our history of arts and education programming.

Museum Talks

82nd Artist Members Exhibition – Museum Mondays: Curatorial Assistant’s Choice with Casey Dalene

Abstract Expressionism Revisited: Selections from the Guild Hall Museum Permanent Collection – Gallery Talk with Joan Marter

Joyce Kubat: My People – Gallery Talk with Joyce Kubat

Tony Oursler: Water Memory – Gallery Talk with Tony Oursler

Syd Solomon: Concealed and Revealed – Gallery Talk with Mike Solomon

Please Send To: Ray Johnson – Gallery Talk with Jess Frost

Sara Mejia Kriendler: In Back of Beyond – Gallery Talk with Sara Mejia Kriendler

Ellsworth Kelly in the Hamptons – Gallery Talk with Phyllis Tuchman

Chuck Close: Recent Works – Talk with Chuck Close and Robert Storr

Hiroyuki Hamada: Sculptures and Prints – Gallery Talk with Hiroyuki Hamada

Robert Motherwell: The East Hampton Years, 1944–1952 – Gallery Talk with Phyllis Tuchman

Rafael Ferrer: Contrabando – Gallery Talk with Rafael Ferrer and Barry Schwabsky

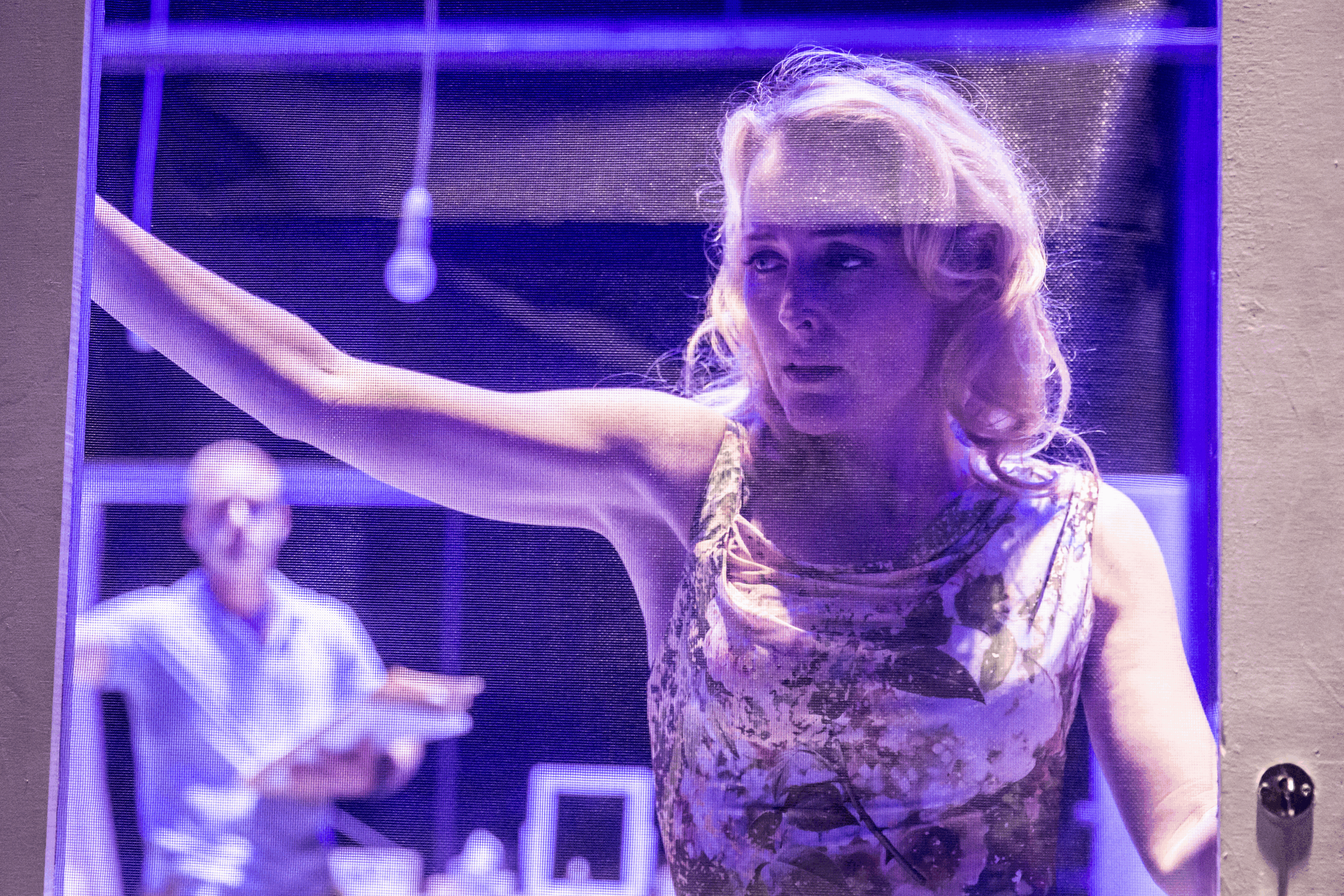

Performances

Melissa Errico: Sondheim Sublime – Full Concert

GE Smith’s PORTRAITS featuring Loudon Wainwright III & Wesley Stace (aka John Wesley Harding) produced by Taylor Barton

Melissa Errico: Sondheim Sublime – “Losing My Mind”

The Django Festival Allstars

Stirring the Pot

Stirring the Pot with Florence Fabricant and Tom Colicchio

Stirring the Pot with Florence Fabricant and Jacques Pépin

Stirring the Pot with Florence Fabricant and Alex Guarnaschelli

Stirring the Pot with Florence Fabricant and Katie Lee

Conversations & Lectures

Artist Dialogue: Clifford Ross with Paul Goldberger and Shirin Neshat

Robert Motherwell: The East Hampton Years, 1944-1952

Panel Discussion with Phyllis Tuchman, Jack Flam, Catherine Craft, and Clifford Ross

Re-Thinking Modern Art: A Preview of the MoMA’s New Collection Galleries with Ann Temkin

In association with the Pollock Krasner House and Study Center

Collector’s Speak: Sotheby’s presents Treasures from Chatsworth

FAPE and the Role of the Artist – Talk with Robert Storr, Tina Barney, Lynda Benglis, Odili Donald Odita, and Joel Shapiro

In association with the Foundation for Art and Preservation in Embassies